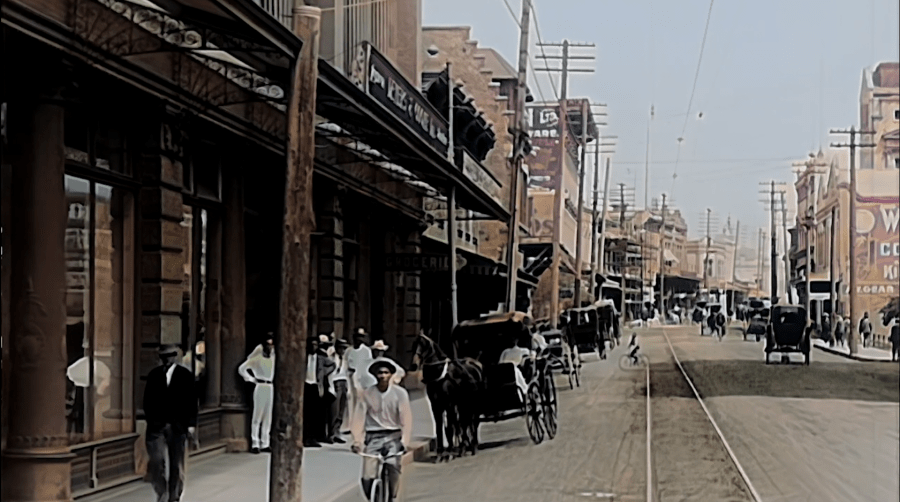

HONOLULU (KHON2) — One hundred and nineteen years ago on Aug. 3, scenes of Honolulu were captured for the very first time by a moving picture invention.

Today, this technology has been taken several steps further by an artist. This technological advancement can only be described with a few words that feel straight out of science fiction: a time machine.

For Arthur Shak, a local centenarian, he can’t believe his eyes — with the help of advanced technology, he is a boy again for a brief few minutes. He can be seen riding the electric streetcar through the Chinatown he knew as a boy.

This time travel magic is the collaboration of three men: Thomas Edison, who invented the kinetograph, Robert Bonine, his cameraman, and Tony Barnhill, who created the digital applications that breathe life into a strip of 119-year-old film.

At the time, Edison didn’t know that sending Bonine to capture moving images in Hawaiʻi would not just preserve history, but make history with a new technology.

With inspirations from the technologies of the 21st century, Barnhill asked the Library of Congress for the most pristine copy of Bonine’s footage, and went to work on his time machine.

“So they sent me a two terabyte hard drive with 44K raw DPS files that I had no idea what to do with,” Barnhill said. “I did a nine frame analysis where it looks forward four frames, backward four frames and looks to see if the dust or particle appears and if it does, it takes it out.”

After making the visuals usable, the next step would be to add a tint. There are hundreds of colorization algorithms, but Barnhill felt the vivid hues just weren’t right, so he added undertone chromaticity the hard way.

“I colorized frame by frame using a photoshop script that opened each file, ran the script, closed the file, saved it, went on to the next times 42,000 files,” Barnhill said. “It ran for weeks, which is why I have 20 terabytes of data.”

This process resulted in about 10,000 hours of standard definition video, and that wasn’t even the hard part.

The original film was silent, but Barnhill grew up learning audio production from his father, Roy Barnhill, who owned a recording studio.

“It allowed me to think about bits and pieces and track, this part can come in, this part can finish that out,” he said.

Being up close and personal with every single frame, Barnhill noticed details. For example, there is only one motor vehicle in the film, a Buick Steamer. He contacted vintage car clubs to get the real sound of a Buick horn.

The process is very tricky and intricate — but worth it for individuals like Shak, who gets to teleport back to a time that was almost forgotten. The newly-resurrected footage got some gears turning for Shak, allowing him to visit some favorite locations lost to time.

“There was Kress Store, next was Cold Custard Ice Cream and next to the stand, a tobacco company. That was my mother’s father’s store,” Shak said.

Shak says he used to work at that store as a teenager selling Camel cigarettes for five cents a pack.

Barnhill’s time machine process has been used on 34 other Edison films, but he has not sold the algorithm — instead, he chooses to give the media to schools, museums and anyone looking to hold on to precious memories.